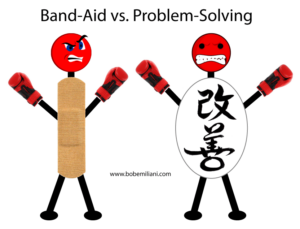

If you observe carefully, you will notice that the people with the best problem-solving skills tend to have poor social skills, while those with the best social skills tend to be poor problem-solvers. The former are curious and go deep into their analysis of a problem to understand its root causes and identify solutions that result in tangible and verifiable improvement. Analysis by the latter is superficial and results in band-aid solutions. Band-aid solutions give the appearance that problems have been solved, and so band-aids are merely political solutions to problems, not an actual solution based on the true source of problems. Band-aid solutions maintains the status quo; they do not result in fundamental improvements to products or processes.

You will also notice that those who are able to create the best band-aid solutions to problems invariably rise to high levels within an organization. To senior leaders, band-aids are as good, if not better, than actually solving the problem, because the status the quo and good appearances are highly valued symbols of expert leadership. The really good problem-solvers — the reformers — remain stuck at lower levels of the organizations where they must fight against the band-aid solution specialists to win favor for their thorough analyses and concordant solutions. And they usually lose.

Because of their deficits in social skills, the best problem-solvers tend to be organizational misfits (detached disturbers of the corporate peace) and are treated as outcasts. Their career path is usually limited; such is the reward for being a good critical thinker — someone who is able to discern the facts and reveal the truth. The band-aid problem-solvers easily fit in, are recognized as “team players” or “key players,” and are treated as favorites within the organization. The favorites, largely indifferent to facts or the truth, quickly rise and are amply rewarded for their limited skill set. It is no surprise that the key requirement for joining an executive team or board of directors is good “good chemistry” — having the requisite social skills. Problem-solving skills are assumed to be “a given” and therefore unimportant to the overall task of corporate supervision.

I have spoken to many business leaders over the years in my job as a university professor. When asked what they are looking for in our graduates, they almost always comment on the need for them to have better soft skills. Rarely do they say students need better critical thinking and problem-solving skills. That makes some sense because, to greater or lesser extents, students have been taught to think critically and problem-solve since elementary school — about 14 years’ worth of education.

The inverse relationship between soft social skills and the critical thinking necessary to be an excellent problem-solver leads to big expensive problems. Business leaders who desire social skills are, knowingly or not, asking for employees to weaken, if not cripple, their critical thinking and problem-solving skills and develop into band-aid problem-solvers. This perfectly fits the needs of business: fast, easy solutions to problems that consume few resources and which require little actual change in thinking and doing. All you have to do is think of the disastrous Boeing 737 Max development program, Wells Fargo’s culture of fraud, Equifax’s data breach, General Electric’s stunning downfall, the Morandi bridge failure, BP oil well explosion, and defective Takata airbags. These are just a few examples illustrating the ubiquity of band-aid problem-solving in business and their catastrophic consequences.

Business is nothing if not a daily flood of problems. Problem that are solved with band-aids invariably recur and perpetually cost the company its resources — all the while the CEO proclaims the need for sparing and judicious use of company resources. Deep problem-solving exposes the truth so that improvement can be made. But if band-aid solutions are the preferred type of solution to business problems, to keep up appearances and maintain the status quo, then the truth is only rarely revealed and problems continue to linger. And when senior leaders finally do decide they want employees to be better problems-solvers, the top of the organization is weighed down band-aid problem-solvers who refuse to learn or practice deep problem-solving. So there are no executive role models for employees to learn from.

This explains why Lean transformation efforts regularly result in the appearance of improvement but fail to achieve material and information flow and Just-in-Time. Occasionally, someone is good at both social skills and problems-solving. But, they are usually not great at either. To achieve flow, you need people who are better at problem-solving than social skills. That means the truth-telling misfits can no longer be treated as outcasts. Yet, treating the problems-solvers as misfits and outcasts has long been institutionalized and is a habit that leaders rarely break.

The further spread of Lean management depends to a large degree on elevating the problem-solving iconoclasts in the organization and intensely training the band-aid solution specialists to become actual problem-solvers. We know from experience that both are difficult to do. So perhaps a solution is for business leaders is to not emphasize the need for soft skills. Instead, the capabilities of new hires and current employees should be tilted towards critical thinking and problem-solving skills because that is what business, given its daily flood of problems, needs most. The perpetual question is this: Can senior leaders welcome the disturbing truth that comes from independent thinkers?